When it comes to lean product development, it doesn’t matter whether you are making wine or motorcycles. Success comes from our ability to tell a story that engages our customers and a product they would line up for.

In Zikheron Yaakov, some 50 kilometers north of Tel Aviv, at the foot of the Carmel mountain range, the Somek Winery uses local grapes to produce unique and customized wines for its clients. Their bottles are neither available in supermarkets nor in selected stores.

Their approach is different from that of a traditional winemaking company: direct contact with clients and custom-made products are at the heart of Somek’s offering, which of course makes their wine design and development process quite interesting.

During a recent visit, owner Barak Dahan told me: “It is important for us to look right into the eyes of anyone who tastes our wine. Whenever I see an unusual response, I immediately discuss it with my wife Hila, so that we can analyze it and adjust our product accordingly.”

The winemaker’s work to produce a specialty wine can be compared to a painter’s ability to turn a vision that is only in the mind of the client into colors and shapes on a canvas, with further adjustments to achieve the desired light effects and shades.

One can of course view the stages of winemaking – from the vineyard to the bottle – as a value stream, but what makes Somek’s case different is that the product development has become a component that cannot be separated from the rest of the process. Barak and Hila try to learn the taste of their customers, in a build-to-order process that I had never seen applied to wine making before. At each stage, they conduct experimental (PDCA) activities, and what they discover informs their next decisions on how to best proceed.

Barak said: “Each action happens within a continuous cycle of choices, from selecting the line of grapes to harvest in the vineyard to the time to harvest them, from adjusting the irrigation to picking the right type of yeast for the mix or deciding how long we are going to age the wine before bottling it.”

Each choice is the result of an experiment used to assess the suitability of each component (to reach the desired taste and aroma) and the feasibility of each step in the process.

This sequence of small choices gradually making up the end product suits the set based concurrent engineering (SBCE) model that is becoming increasingly popular in other industries where lean product development is in use. Indeed, Somek’s decision-making process is guided by the sequence of experiments: each stage sees a set of possibilities to choose from, which in turn inform the production process.

It was very interesting to see LPPD principles applied the winemaking process to ensure the end product is exactly what the customer wants – customized wine is certainly something I would call a “cool product” a customer would covet – which is, of course, what every company ultimately strives for (just ask Apple, Tesla, Pixar-Disney or Harley-Davidson).

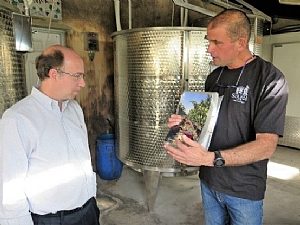

Speaking of Harley-Davidson, on my visit to Somek I was joined by John Drogosz, who had previously consulted for the motorcycle-maker as they were undergoing a lean product development transformation. John seemed very interested in Somek’s ability to understand the real purpose of their winery and to design and develop a value proposition that offers clients an active engagement (a good story), rather than just a product. Clearly, he saw things in common between Somek’s processes and Harley-Davidson’s.

the motorcycle-maker as they were undergoing a lean product development transformation. John seemed very interested in Somek’s ability to understand the real purpose of their winery and to design and develop a value proposition that offers clients an active engagement (a good story), rather than just a product. Clearly, he saw things in common between Somek’s processes and Harley-Davidson’s.

At Harley, he told us, there is a team of three “tasters” who participate in the development and production process that leads to the creation of new motorcycles models. At each stage of the development, the team investigates the concept of “cool” according to those who want to join the community of Harley riders. The taster team is very active during the investigation, learning and product design stages, and continues on as a partner in decision-making throughout the development and production processes.

Interestingly, the same process can be seen at Pixar Studios, where a Creative Team is tasked with the taster-like job of defining what makes a “cool” animated movie and producing it. The team, which is coordinated by the movie creator (whose job is similar to that of the Chief Engineer in LPPD), is a creation of CCO (Chief Creative Officer) John Lasseter. It has no real hierarchy and is interested in dialogue and in feedback coming from anyone connected with the production – their approach is in many ways similar to the development process at Somek Winery, which is lean product and process development.

Lasseter once said: “If you are sitting in your minivan, playing your computer animated films for your children in the back seat, is it the animation that is entertaining you as you drive and listen? No, it’s the storytelling. That’s why we put so much importance on story. No amount of great animation will save a bad story.”

It’s not how we package the product that will ensure its success, but whether we are able to create it in a way that responds to a customer need: competitiveness comes from our ability to engage our customers’ mind, which has come to overshadow traditional marketing campaigns.

It doesn’t matter whether you make wine, motorcycles or animated movies… a “good story” is a necessary condition for the development of a good product, but it is not enough: you also need “story designers,” creative people who are partners in the development and production process, one experiment at a time. They will be the ones that will make a product exactly what your customers want.

Boaz Tamir, ILE.

Leave a Reply